大家好/ Hello everyone

2 weeks ago we had a crazy news cycle. Besides the ongoing pandemic, a container of the same size as a skyscraper got stuck in the Suez Canal, one of the most important routes for international shipping trade. As a crisis goes, it resulted in huge economic losses, but, most importantly, it gave us good memes. The whole drama took almost a week to be solved, and the more I read about it, the more I was thinking about what the heck had happened to China's touted Belt and Road Initiative? Let me explain.

During the months of September & October 2013, two announcements were made by the Chinese leadership. The first one, made in Kazakhstan, was focused on reviving the old Silk Road connections, the legendary land route through which brave merchants traveled for centuries, and that connected China with Central Asia and even Europe. It is the same land route that Marco Polo traveled and documented during the Chinese Yuan Dynasty. The second announcement, made in Indonesia, shared to the world the vision of a 21st century Maritime Silk Road, also with historical significance in mind.

One thing to keep in mind is that, Indonesia considers itself a major maritime hub and is strategically located along with two of the world's main shipping chokepoints, the Malacca and the Sunda straits. Secondly, although it is not that well-known to foreigners, China was a sizable maritime power at a point during its long history. During the Ming Dynasty, the famous explorer Zheng He (1371-1433), set forth with a sizable armada, from the ports of nowadays Fujian Province, seven times in voyages mainly focused on promoting trade and expanding China's network of tributary states (basically the states that acknowledged the Chinese Emperor as superior and provided yearly "donations").

As our minds are already on the topic of water routes and their economic significance, this week I will try to summarize what was the initial goal of the Chinese Maritime Silk Road 2.0, what kind of projects it approached, some issues it faced, and its possible future. As usual, I hope you enjoy the article and, if you do, subscribe to the newsletter to get more content like this. Feel free to share any feedback on Twitter (@jorgegoncalo) or in the comments section.

Index:

Intro

What is the MSR?

The influence of the Hambantota port

Will the MSR succeed?

What is the MSR?

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) is a group of development projects, spread throughout key areas of interest for the Chinese government, with an emphasis on the development of the blue (oceanic) economy, enhancing shipping networks, cooperation in common security issues (i.e pirates), and supplementing the land-based Belt initiative.

Sounds like a lot of stuff right? Let’s break it down.

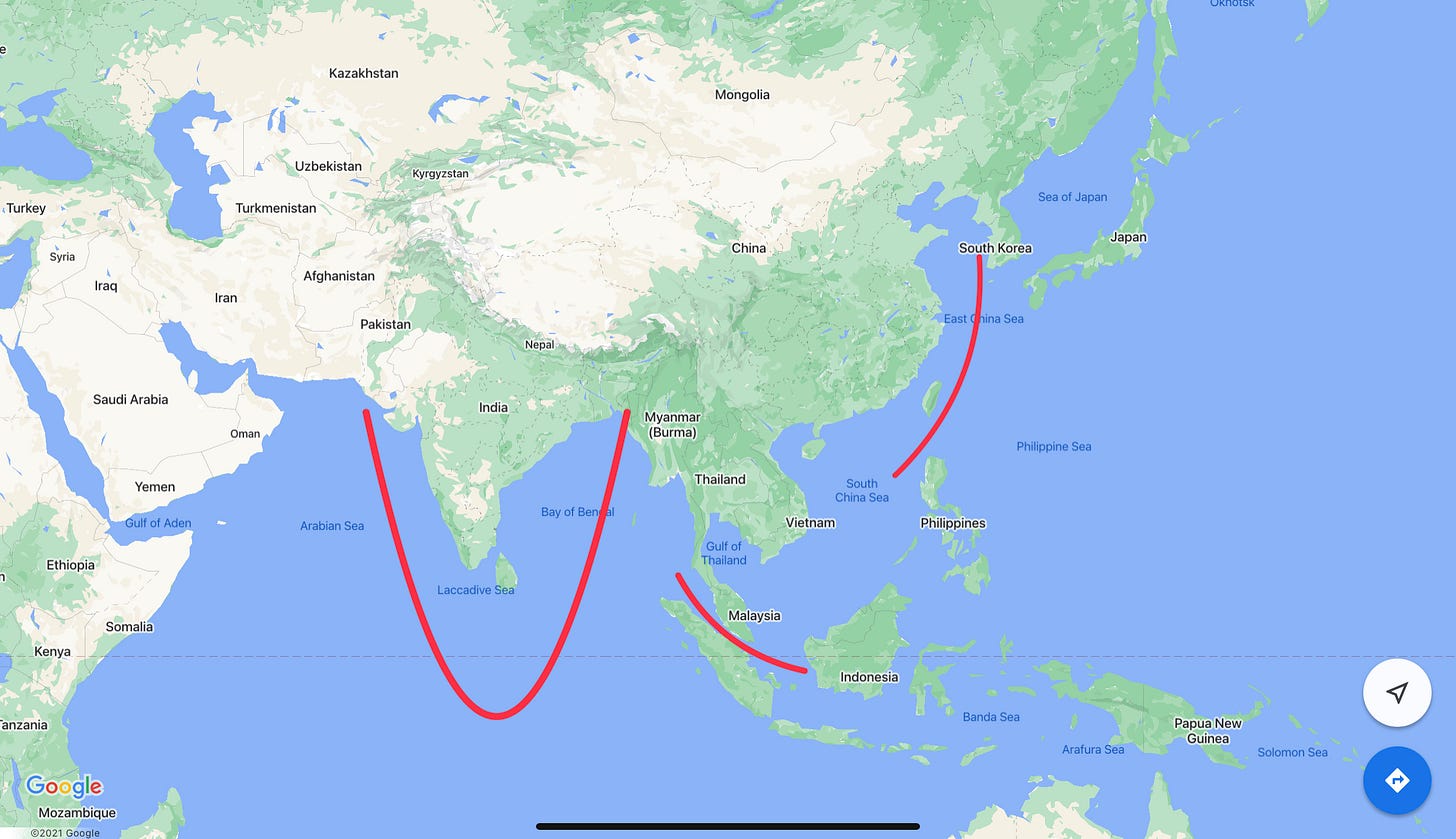

The MSR's focus areas are Southeast Asia, Indian Ocean, Oceania, Middle East, and the Mediterranean Sea, through its 3 routes:

1- China - Indian Ocean - Africa - Mediterranean Sea: Arguably the most important one, but also the one with the biggest number of security issues and geographical chokepoints, i.e the Malacca strait, from where 85% of China's oil transport goes through, or the Suez Canal, which processes 80% of the Eurasian maritime cargo.

2- China - Oceania - South Pacific: Lately hampered by the diminishing relationship levels between Australia and China.

3- China - Arctic Ocean - Europe: Of particular interest in the future due to going through primarily cooperative countries' waters, like the Russian Arctic shipping routes, but still frozen for most of the year (China has even been investing in icebreakers though).

The goals of the MSR are:

1- strengthening international maritime cooperation;

2- improving shipping service networks among countries along the MSR;

3- establishing joint international and regional shipping centers.

Countries along the route are encouraged to strengthen their ties by forming port partnerships and partnering with sister ports (i.e the Chinese-controlled Pakistani Gwadar's sister port of Chabahar in Iran). Chinese companies are encouraged to invest in port development and services. As Xi Jinping said:

"It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia".

Chinese companies are focusing on investing in what are called transshipment ports. Basically, these are hubs that can host the largest type of container ships, and that can be used as logistic hubs, from where containers are distributed to smaller ships that will continue the trip to the product's final destination.

Let's take the Piraeus port in Greece as an example. The Chinese government considers Piraeus port, in Greece, to be the main entry point for Chinese exports to Europe's Southern, Eastern, and Central regions, as well as a key gateway for seaborne shipping through and around the Mediterranean Sea. This project is one of the key MSR investments, and overall considered a "win-win" project by the Greek government.

The Chinese state-owned Cosco Shipping has been investing since 2009 in Greece's biggest port. Cosco acquired a 35-year concession to multiple container piers in the port and bought an overall 51% majority stake in 2016. After taking control of these piers, a clear efficiency contrast could be seen between the Chinese and the Greek sides, the first rose its containers per hour processing rate from 10/12 to 44 per hour and only employed 270 workers, while the latter had a lower rate and had 1300-strong workforce.

Piraeus works as a hub from where containers are further distributed in the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Black seas. A hub that connects China with Europe in a faster way than the traditional port or Rotterdam for example (Europe's biggest port).

The route that connects the China South Sea with the Mediterranean is the crucial node of the MSR. Besides the energy and food supply chains, the so-called gateway ports of Gwadar in Pakistan and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar stimulate the redevelopment of China's terrestrial economy by linking China's less-developed inland provinces (Yunnan/Guangxi and Xinjiang) to the Indian Ocean via the BRI's (Belt and Road Initiative) economic corridors. Gwadar port, in Pakistan, will enable oil from the Middle East to be transported through a pipeline to Xinjiang. This means a reduction of the traditional 12,000km trip to 2395.

China has a big coast but also a lot of different players surrounding it and, actually, that is why it sometimes tries to be overly obstinate in regards to its claims in the South China Sea. The country is surrounded by several navy powers in its immediate waters (South Korea, Japan, and the US), a conglomerate of smaller but yet key positioned countries in South East Asia, and after all that India, which dominates the South Asian region and clearly sees the Indian Ocean as its "backyard".

On the other hand, with the Arctic Route, it is also important to take in mind China's goal to be more involved in the Arctic Circle both scientifically, in terms of climate-change research, as well as politically as a "near-Arctic state". This is China's Polar Silk Road.

The influence of the Hambantota Port

There is a sort of defining moment in the MSR's history from which the perception of countries involved in the project greatly changed. Before the Hambantota scandal, for example, the MSR was seen as a viable solution for countries in South Asia that didn't want to be too dependent on Indian investment. In July 2017 though, the Sri Lankan government signed a 99-year lease of the container port of Hambantota to a Chinese-majority-owned company after it could not pay the loans it took to develop it.

This instance, still discussed today, was called a case of "debt-trap diplomacy", with the implication that China acted in order to acquire this port that, albeit not being nearly as important as the port in Colombo in terms of trade, sits at the Southern tip of Sri Lanka, and overlooks crucial Indian Ocean shipping routes. The same label was called upon again in debt issues with Zambia and other African countries.

The blunt reality is that the true intentions don't really matter here. MSR's image, especially in Southeast Asia and Africa, was deeply affected. In 2018, the newly-elected Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad canceled a MSR-related mega-project of a railway that would traverse the Northern part of the country. The reason? Fear that the huge costs of it would send Malaysia in a spiral of debt, and deepen Chinese interests in the region. It took a year of negotiations for the project to resume, with a 1/3 cut in its costs.

Of all the Southeast Asian states, Vietnam remains the most skeptical about the MSR project. Its levels of involvement have been affected by a populace that strongly resents Chinese presence in the country. On the other hand, Laos's landlocked economy is heavily reliant on Chinese investment and trade to develop. It is a crucial hub for the BRI due to its position between China, Vietnam, and Thailand. Given the country's tense ties with the United States, Cambodia sees the BRI as advantageous, especially in terms of meeting infrastructure needs and diversifying economic and political alliances.

Aside from debt-related issues, the MSR has sparked concerns about the quality of Chinese imports, trade imbalances geared towards China, the recurring usage of Chinese labor instead of the domestic workforce, and low-quality Chinese construction. Myanmar's government has scaled back the deep-water port project in Kyaukpyu (the one that was to be linked with Yunnan), citing a concern about demand rather than debt.

Will the MSR succeed?

At the moment the word "Silk Road" means a conjecture of partnership agreements, and investment in projects that promote economic networks. This can be adapted in a land-focused Belt, a maritime Road, and nowadays even in "Green", "Health" and "Polar" geared developments.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the MSR was overall a success. Although China had to carefully manage security and economic fears from different areas, it managed to steadily expand, even reaching the Caribbean (with the case of Trinidad and Tobago). Also, Chinese investments in the MSR are not merely focused on ports and shipping lanes, but also on bringing economic activity from landlocked countries through railway connections, like in Ethiopia.

The fact is that China wants to continue to promote these "win-win" agreements and in general the development of economical networks, as it also helps Chinese exports. Most importantly though, the MSR is a way for China to build solutions that guarantee food & energy supply, diversify shipping lanes, and connect less-developed Chinese provinces like Yunnan and Xinjiang with the Indian Ocean (and directly skip the South China Sea and Southeast Asia).

For China, given the widening economic growth divide between its regions, the United States' pivot back to the APAC region, the Quad's (US, Japan, India, Australia) growing cooperation, and ASEAN countries' maritime disputes, the building of the Maritime Silk Road, if it is to succeed, must focus on the goal set by Section II of Chapter 41 of the most recent Five Year Development Plan: to "Expand the brand influence of Silk Road Shipping".

Was this article useful?

My name is Jorge and China Abridged is where I write weekly about Chinese technology and society. I have a B.A in Asian Studies with the University of Lisbon, won a scholarship from the Confucius Institute for academic excellence, and lived for 2 years in the Middle Kingdom.

For the past 4 years, I have been involved with one of the biggest fintech startups in the world and now I spend my time honing my language skills, perusing articles about 中国, and perfecting my RSS feed.

You can check out all past issues here. Also, I would be extremely thankful if you shared this article with your friends and colleagues if you found it interesting.

Any suggestions for topics or feedback? Let me know on Twitter 🐦 @jorgegoncalo.